The Green Bond Endorsed Projects Catalogue - China's Green Taxonomy

A Guide to Sustainable Finance Classification in the World's Second-Largest Economy

Introduction

As the world's largest carbon emitter and second-largest economy, China's approach to sustainable finance has profound implications for global climate action. China's Green Taxonomy—officially known as the Green Bond Endorsed Projects Catalogue (绿色债券支持项目目录)—represents one of the most significant frameworks for defining and directing green investments in a major economy. Established to channel capital toward environmentally beneficial projects and activities, the Chinese taxonomy has evolved significantly since its inception and now forms a cornerstone of the country's broader ecological modernisation strategy.

Historical Context and Development

Early Green Finance Initiatives (2012-2015)

China's formal green finance system began taking shape in 2012 when the China Banking Regulatory Commission (now part of the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission or CBIRC) issued the Green Credit Guidelines, marking the first regulatory push toward environmental considerations in financial decision-making (PBOC et al., 2016). However, the concept of a comprehensive green taxonomy emerged in response to the explosive growth of China's green bond market following the country's climate commitments ahead of the 2015 Paris Climate Conference.

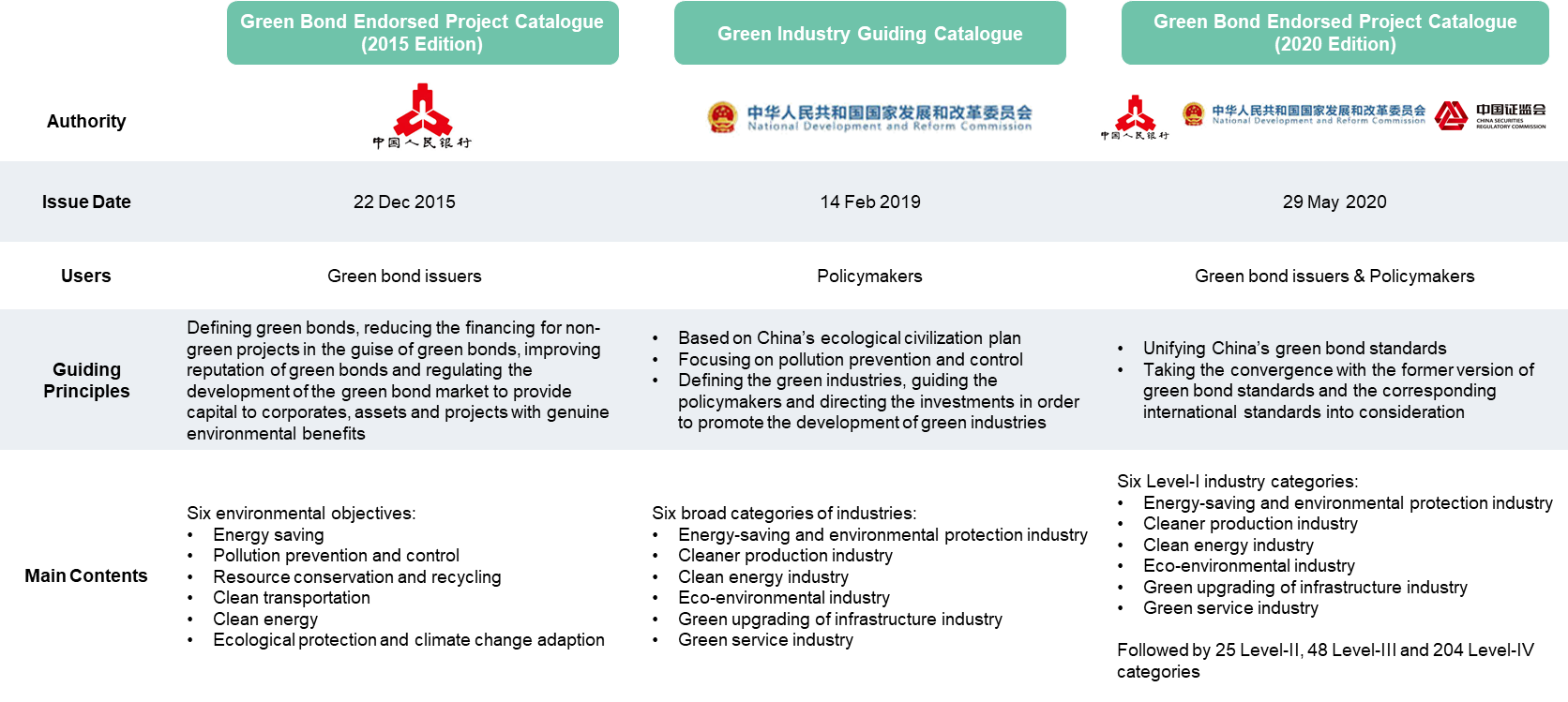

In December 2015, two separate green bond catalogues were issued:

The Green Bond Endorsed Project Catalogue, published by the Green Finance Committee of the China Society for Finance and Banking under the People's Bank of China (PBOC)

The Guidelines for Issuing Green Bonds, released by the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC)

This dual-catalogue system created market confusion and highlighted the need for a unified approach to green finance classification (Wang et al., 2020).

Evolution Toward a Unified Taxonomy (2016-2019)

Between 2016 and 2019, China's green finance system underwent significant development:

In August 2016, the PBOC and six other government agencies jointly issued the Guidelines for Establishing the Green Financial System, solidifying the role of the Green Bond Endorsed Project Catalogue as a foundational document for green finance (PBOC et al., 2016)

In 2017, the Asset Management Association of China released guidelines for green investment by securities investment funds, referencing the PBOC-backed catalogue

In 2018, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) issued guidelines for green bond issuance by listed companies, also referencing the PBOC catalogue

During this period, China became the world's largest issuer of green bonds, with annual issuance reaching $42.8 billion in 2018 (Climate Bonds Initiative, 2019). However, the continued existence of multiple standards—with different scopes, particularly regarding clean coal and fossil fuel efficiency projects—created market inefficiencies and hindered international alignment.

The 2020 Unified Taxonomy

In May 2020, the PBOC, NDRC, and CSRC jointly published a consultation draft of a revised, unified Green Bond Endorsed Project Catalogue (PBOC et al., 2020). The final version, released in April 2021, represented a significant milestone in China's green finance framework by:

Establishing a single, nationwide standard for green bonds.

Removing "clean utilisation of coal" from the list of eligible projects.

Introducing more stringent criteria for energy efficiency improvements.

Aligning more closely with international standards.

This revised catalogue became effective on July 1, 2021, and marked China's first comprehensive and unified green taxonomy (PBOC et al., 2021).

Main Components of China's Green Taxonomy

Structure and Classification System

The 2021 Green Bond Endorsed Project Catalogue adopts a three-tier classification system:

Level I: Six broad categories of green projects:

Energy saving and environmental protection

Clean production

Clean energy

Ecological protection and climate change adaptation

Green infrastructure

Green services

Level II: 21 subcategories under the six main categories.

Level III: Detailed descriptions of 204 specific project types with technical criteria.

For each eligible project type, the catalogue provides:

Project definition and scope.

Technical standards and thresholds.

Environmental benefit requirements.

Reference to national or industry standards.

Environmental Objectives and Focus Areas

Unlike the EU Taxonomy's six environmental objectives, China's Green Taxonomy does not explicitly define separate environmental objectives. Instead, its six Level I categories serve as both classification categories and implicit environmental objectives. However, analysis of the technical criteria reveals emphasis on:

Pollution reduction (particularly air, water, and soil pollution).

Energy efficiency and conservation.

Carbon emission reductions.

Ecosystem protection and restoration.

Resource conservation and circular economy principles.

This focus reflects China's domestic environmental challenges and priorities, with significant attention to pollution control alongside climate change mitigation (Climate Policy Initiative, 2020).

Technical Criteria and Thresholds

Technical criteria in China's Green Taxonomy generally take three forms:

Compliance-based criteria: Reference to specific national or industry standards (e.g., projects must meet Energy Conservation Evaluation Standards for Civil Buildings GB/T 50668).

Performance-based criteria: Quantitative thresholds for environmental performance (e.g., energy consumption per unit of product at least 15% below national average).

Technology-based criteria: Lists of approved technologies or processes (e.g., specific renewable energy generation technologies).

The technical requirements tend to be less granular than those in the EU Taxonomy but often reference comprehensive Chinese national standards that contain detailed specifications (International Platform on Sustainable Finance, 2021).

Comparison with International Standards

China-EU Common Ground Taxonomy

In November 2021, the International Platform on Sustainable Finance (IPSF), co-led by China and the EU, published the Common Ground Taxonomy (CGT), which analyses the similarities and differences between the Chinese and EU taxonomies (IPSF, 2021). Findings include:

Approximately 80% overlap in climate change mitigation activities.

Significant commonalities in renewable energy and manufacturing criteria.

Different approaches to transportation and buildings.

Varying levels of technical detail and stringency.

The CGT represents a significant step toward international harmonisation of green finance standards and offers a potential bridge between the world's two leading taxonomy systems.

Main Differences from the EU Taxonomy

Several structural differences distinguish China's Green Taxonomy from the EU Taxonomy:

Environmental objectives: While the EU system has six clearly defined environmental objectives, China's system combines classification categories with implicit environmental goals.

Do No Significant Harm (DNSH) principle: The EU Taxonomy requires that activities meeting one environmental objective must not significantly harm the other five objectives. China's taxonomy does not have an explicit DNSH principle, although some sector-specific requirements address environmental trade-offs.

Minimum safeguards: The EU Taxonomy requires compliance with social safeguards based on international standards. China's taxonomy focuses primarily on environmental criteria with limited social considerations.

Coverage of transition activities: China's taxonomy includes more transition activities in carbon-intensive sectors, reflecting its development stage and energy mix (Climate Policy Initiative, 2020).

Mandatory disclosure: While the EU has established a comprehensive disclosure regime linked to its taxonomy, China's disclosure requirements are still evolving.

Implementation and Market Impact

Regulatory Framework and Disclosure Requirements

China has developed an increasingly robust regulatory framework around its Green Taxonomy:

In January 2022, the PBOC issued a notice requiring financial institutions to report the environmental impact of green bonds, including carbon emission reductions (PBOC, 2022).

In February 2022, the CBIRC published guidelines for financial institutions to assess, monitor, and manage environmental and climate risks.

In July 2022, the CSRC strengthened ESG disclosure requirements for listed companies, encouraging alignment with the Green Taxonomy.

However, unlike the EU's mandatory disclosure regime, China's approach has been more gradual, with an initial focus on green bonds and bank lending before expanding to broader corporate disclosure.

Market Growth and Composition

Since the introduction of the unified taxonomy, China's green finance market has shown significant growth:

Green bond issuance reached approximately 600 billion yuan ($93.5 billion) in 2021, making China one of the largest green bond markets globally (CBI and CCDC, 2022).

Green loans outstanding exceeded 15 trillion yuan ($2.3 trillion) as of end-2021 (PBOC, 2022).

By sector, energy, transportation, and pollution prevention projects account for approximately 70% of green bond proceeds (CBI and CCDC, 2022).

The removal of clean coal projects from the taxonomy has reshaped the market composition, with renewable energy projects taking a larger share of green financing.

Integration with Related Policies

The Green Taxonomy has been integrated with several other sustainable finance and climate policies:

The national carbon market (Emissions Trading Scheme), which began operation in July 2021.

The environmental information disclosure system for financial institutions.

Green finance incentive mechanisms, including preferential interest rates and refinancing opportunities from the PBOC.

Provincial green finance pilot zones, which often reference the national taxonomy with additional local criteria.

This policy integration creates a more comprehensive ecosystem for sustainable finance in China (NGFS, 2022).

The Carbon Neutrality Investment and Financing Taxonomy

Development and Purpose

In response to China's carbon peaking and carbon neutrality goals (commonly known as the "30-60" targets—carbon peaking before 2030 and carbon neutrality before 2060), China expanded its taxonomy system in 2022 with the Carbon Neutrality Investment and Financing Taxonomy (中国碳中和投融资分类目录).

Released in May 2022 by the China Enterprise Reform and Development Society (a think tank affiliated with the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission) and Tsinghua University, this taxonomy:

Broadens the scope beyond traditional "green" activities to include transition activities in carbon-intensive sectors.

Provides specific guidance for financing activities aligned with the carbon neutrality goal.

Creates a three-category classification system (Tsinghua University Center for Finance and Development, 2022).

Three-Category System

The Carbon Neutrality Taxonomy introduces a more nuanced approach to sustainable activities:

Green/Low-carbon Activities: Similar to projects in the Green Bond Catalogue, these activities have minimal carbon footprints (e.g., renewable energy, afforestation).

Transition Activities: Projects that significantly improve the carbon efficiency of carbon-intensive industries but don't yet achieve zero emissions (e.g., efficiency improvements in conventional power generation, low-carbon steel manufacturing).

Enabling Activities: Projects that enable emission reductions in other sectors (e.g., energy storage, carbon capture and storage technologies, climate monitoring).

This system acknowledges the reality of China's development stage and energy structure while creating pathways for high-emission sectors to contribute to the net-zero transition (IIGF, 2022).

Local Implementation and Innovation

Provincial Green Finance Pilots

Since 2017, China has established green finance pilot zones in nine provinces and regions, including Guangdong, Zhejiang, Jiangxi, Guizhou, and Xinjiang. These pilots have served as testing grounds for taxonomy implementation and innovation:

Guangdong has developed supplementary standards for the Greater Bay Area's green industries.

Zhejiang has experimented with digital platforms for taxonomy-based green project verification.

Huzhou city (in Zhejiang) has created a pioneering "environmental credit rating" system linked to the taxonomy that influences financing terms.

These local innovations provide valuable implementation experience for potential national adoption (PBOC, 2021).

Digital Innovations in Taxonomy Application

China has been at the forefront of applying digital technologies to taxonomy implementation:

The PBOC has developed a green finance information management system that automates classification of green loans.

Several banks have integrated the taxonomy into their loan management systems using artificial intelligence.

Blockchain-based verification of green assets has been piloted in Guangdong and Shanghai.

Big data approaches have been used to assess corporate alignment with taxonomy criteria.

These digital applications enhance the efficiency and reliability of taxonomy-based classifications (NGFS, 2022).

Challenges and Controversies

Transition Versus Transformation

A significant debate surrounds the inclusion of transition activities, particularly in carbon-intensive sectors:

Critics argue that China's approach may delay genuine transformation by supporting incremental improvements in high-emission industries.

Defenders contend that China's development stage and energy reality necessitate a pragmatic approach to transition.

The Carbon Neutrality Taxonomy attempts to address this by distinguishing between truly green activities and transition activities.

This tension reflects broader international debates about the role of transitional approaches in sustainable finance (Wang et al., 2022).

Data Quality and Verification

Implementation challenges include:

Limited third-party verification requirements compared to international standards.

Inconsistent environmental data disclosure by companies.

Varying technical capacity across financial institutions, particularly smaller regional banks.

Gaps in monitoring and enforcement mechanisms.

Efforts to address these challenges include capacity building programs for financial institutions and the development of a more robust green finance verification industry (CBI, 2022).

International Harmonisation Versus Local Relevance

China faces the challenge of balancing:

International alignment to facilitate cross-border green investment and prevent "green balkanisation".

Domestic relevance to address China-specific environmental challenges and development priorities.

Technical feasibility given the country's institutional capacities and data availability.

"Green balkanisation" refers to the risk of creating fragmented, inconsistent standards for what qualifies as "green" or sustainable investment across different countries or regions. In this context, it means that if each nation or region develops its own unique set of green investment criteria and regulations, it could hinder cross-border investments and collaboration. Essentially, instead of having a unified, internationally recognised framework for green investments, the market would become divided into separate, localised systems. This fragmentation can lead to confusion, higher compliance costs, and reduced market efficiency—issues that China is trying to avoid as it seeks to balance international alignment with its own domestic environmental and development priorities.

The Common Ground Taxonomy represents an attempt to navigate these competing objectives, but significant work remains to achieve meaningful international harmonisation while maintaining locally appropriate standards (IPSF, 2022).

Future Directions

Extension to "Transition Finance" Framework

Building on the Carbon Neutrality Taxonomy, China is developing a more comprehensive framework for transition finance:

In March 2023, the PBOC and other regulators issued guidelines for financial institutions to support industrial low-carbon transitions.

Industry-specific transition pathways are under development for eight high-emission sectors, including power, steel, and cement.

A transition bond standard is expected to be released in 2023-2024.

This transition framework aims to mobilise financing for hard-to-abate sectors' decarbonisation (IIGF, 2023).

ESG Disclosure Integration

China is moving toward greater integration of taxonomy-based disclosure with broader ESG reporting:

The CSRC has indicated plans for mandatory ESG disclosure for listed companies by 2025.

The Ministry of Ecology and Environment is developing environmental information disclosure standards.

Financial regulators are considering climate-related financial disclosure requirements aligned with international standards.

This integration would strengthen the implementation of the taxonomy by improving data availability and quality (SynTao, 2022).

Role in the Belt and Road Initiative

China's Green Taxonomy is increasingly influencing overseas investment through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI):

The Green Investment Principles for the Belt and Road (signed by over 40 financial institutions) reference the Chinese taxonomy.

Several Chinese banks have begun applying taxonomy criteria to overseas project financing.

The BRI Green Development Coalition has proposed a "traffic light system" for projects based partially on taxonomy criteria.

These developments suggest an expanding international influence for China's green finance standards beyond its domestic market (Wang et al., 2022).

Implications for Different Stakeholders

For Chinese Financial Institutions

Need to develop expertise in applying taxonomy criteria across lending and investment portfolios.

Opportunity to develop innovative green financial products based on taxonomy classifications.

Requirement to enhance environmental risk management systems and disclosure practices.

Competitive advantage for institutions with advanced taxonomy implementation capabilities.

For International Investors

Need to understand both similarities and differences between Chinese and home-country taxonomies.

Opportunity to access China's rapidly growing green finance market.

Challenge of navigating varying disclosure standards and verification practices.

Potential for regulatory arbitrage if significant taxonomy differences persist (Regulatory arbitrage is a practice of taking advantage of loopholes in regulations to gain a competitive advantage. It can involve restructuring transactions, moving operations to another jurisdiction, or financial engineering).

For Chinese Corporations

Increasing pressure to align business strategies with taxonomy-defined green activities.

Access to potentially preferential financing for taxonomy-aligned projects.

Growing disclosure expectations regarding taxonomy alignment.

Competitive implications as taxonomy criteria influence market access and financing costs.

For Policymakers

Opportunity to use taxonomy as a tool for implementing broader environmental and climate policies.

Challenge of balancing international harmonisation with domestic priorities.

Need to develop robust monitoring and enforcement mechanisms.

Potential to use taxonomy as a basis for green fiscal policies and incentives.

Conclusion

China's Green Taxonomy represents a cornerstone of the world's largest emerging economy's sustainable finance framework. From its initial fragmented approach to the current comprehensive system, the taxonomy has evolved significantly to balance international alignment with domestic priorities. The addition of the Carbon Neutrality Taxonomy has further expanded its scope to address transition activities, reflecting China's pragmatic approach to its unique development challenges.

As global sustainable finance standards continue to evolve, China's approach offers important lessons about implementing taxonomy systems in diverse economic contexts. The ongoing harmonisation efforts, particularly through the Common Ground Taxonomy with the EU, represent crucial steps toward a more coherent global sustainable finance architecture.

For stakeholders navigating China's green finance landscape, understanding the taxonomy's technical requirements, implementation mechanisms, and future trajectory is essential. As China pursues its carbon neutrality goal and ecological civilisation vision, the taxonomy will likely play an increasingly central role in channeling investment toward sustainable economic activities, both domestically and along the Belt and Road.

References

China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC). (2012). Green Credit Guidelines. Beijing: CBRC.

China Enterprise Reform and Development Society & Tsinghua University. (2022). Carbon Neutrality Investment and Financing Taxonomy. Beijing: CERDS.

Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI). (2019). China Green Bond Market 2018. London: CBI.

Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) & China Central Depository & Clearing Co. (CCDC). (2022). China Green Bond Market Report 2021. London: CBI.

Climate Policy Initiative (CPI). (2020). Comparing China's Green Definitions with the EU Sustainable Finance Taxonomy. San Francisco: CPI.

International Institute of Green Finance (IIGF). (2022). China Carbon Neutrality Taxonomy: Analysis and Implications. Beijing: IIGF.

International Institute of Green Finance (IIGF). (2023). China's Transition Finance Framework. Beijing: IIGF.

International Platform on Sustainable Finance (IPSF). (2021). Common Ground Taxonomy – Climate Change Mitigation. Brussels: European Commission.

International Platform on Sustainable Finance (IPSF). (2022). Common Ground Taxonomy – Extended to Adaptation. Brussels: European Commission.

Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS). (2022). Case Studies of Environmental Risk Analysis and Integration into Central Banks' Operations. Paris: NGFS.

People's Bank of China (PBOC). (2021). Report on Green Finance Development in Pilot Zones. Beijing: PBOC.

People's Bank of China (PBOC). (2022). Green Bond Environmental Information Disclosure Guidelines. Beijing: PBOC.

People's Bank of China (PBOC), China Banking Regulatory Commission, China Securities Regulatory Commission, China Insurance Regulatory Commission, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Environmental Protection, & National Development and Reform Commission. (2016). Guidelines for Establishing the Green Financial System. Beijing: PBOC.

People's Bank of China (PBOC), National Development and Reform Commission, & China Securities Regulatory Commission. (2020). Consultation Draft of Green Bond Endorsed Projects Catalogue (2020 Edition). Beijing: PBOC.

People's Bank of China (PBOC), National Development and Reform Commission, & China Securities Regulatory Commission. (2021). Green Bond Endorsed Projects Catalogue (2021 Edition). Beijing: PBOC.

SynTao. (2022). China ESG Development Report 2022. Beijing: SynTao.

Tsinghua University Center for Finance and Development. (2022). Carbon Neutrality Investment and Financing Taxonomy: Technical Report. Beijing: Tsinghua University.

Wang, B., Ke, X., Boissinot, J., Opršal, V., Uhlenbruch, C., Raquim, A.S., & Stein, P. (2020). Comparing Green Definitions: China versus the EU. In Sustainable Recovery and Rethinking the Financial System. Paris: Financial Centers for Sustainability.

Wang, Y., Zadek, S., Chen, X., & Yang, F. (2022). Financing China's Transition to Carbon Neutrality. Beijing: International Institute of Green Finance.