What are Social Bonds?

Introduction, Structure, Principles, Case-Studies, Benefits, Challenges, and Opportunities

The global financial system is undergoing a profound transformation. There's a growing recognition that capital allocation decisions have real-world consequences, not just financial ones. Sustainable finance, encompassing Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) considerations, has moved from the periphery to become a central theme in investment and lending. Within this broad church, specific instruments have emerged to target particular goals.

Social Bonds are a prominent example. They are fixed-income instruments, fundamentally similar to conventional bonds, but with one critical distinction: the proceeds raised are exclusively earmarked for financing or refinancing new or existing projects with positive social outcomes. They represent a direct mechanism for investors to support initiatives addressing societal challenges and improving livelihoods, particularly for target populations often underserved by traditional finance.

Their emergence reflects a deeper understanding that economic progress cannot be divorced from social well-being. Issues like poverty, inequality, lack of access to essential services (healthcare, education, housing), and unemployment are not merely social problems; they are economic impediments and sources of systemic risk. Social Bonds provide a structured, transparent way for capital markets to play a role in tackling these challenges, aligning financial returns with measurable social progress. They are a tangible expression of capital serving a social purpose, increasingly relevant in the context of achieving the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Social Bond Principles (SBP)

While the concept of socially responsible investing has existed for decades, the formalisation of specific 'use-of-proceeds' bonds gained traction first with Green Bonds. Social Bonds followed, borrowing the structural integrity developed for their green counterparts but focusing explicitly on social objectives.

The cornerstone of the global Social Bond market is the Social Bond Principles (SBP), voluntarily convened and administered by the International Capital Market Association (ICMA). First published in 2017 and updated periodically to reflect market evolution, the SBP provide guidelines that promote transparency, disclosure, and integrity. They are not a rigid regulation but serve as the globally accepted market standard, fostering trust among issuers, investors, and intermediaries. Adherence to the SBP is crucial for the credibility of a Social Bond issuance.

The SBP are built around four core components:

1. Use of Proceeds

This is the heart of a Social Bond. The principles mandate that all funds raised must be allocated to ‘Eligible Social Projects’. These projects should provide clear social benefits, which should be assessed and, where feasible, quantified by the issuer. The SBP provides an indicative, non-exhaustive list of eligible categories (discussed further below) and emphasises identifying the target populations expected to benefit.

2. Process for Project Evaluation and Selection

Issuers must clearly communicate their social objectives and the process used to determine how projects fit within the eligible categories. This includes outlining the eligibility criteria, how projects are identified and screened, and any relevant environmental and social risk management processes applied during selection. Transparency regarding the issuer's strategic social goals is key.

3. Management of Proceeds

The net proceeds of the bond must be tracked and managed transparently, often credited to a sub-account or otherwise appropriately monitored by the issuer. The issuer should have internal controls in place to ensure proceeds are allocated only to Eligible Social Projects. Pending allocation, clear disclosure on the temporary placement of unallocated funds is recommended. Periodic verification of this internal tracking and allocation by an external auditor is encouraged.

4. Reporting

Issuers should provide readily available, up-to-date information on the allocation of proceeds, renewed at least annually until full allocation. Crucially, issuers are expected to report on the social impact of the projects funded. This reporting should ideally include both qualitative descriptors and quantitative performance measures (metrics), outlining the methodology and assumptions used.

Beyond these core components, the SBP strongly recommend two further elements for enhanced transparency and credibility:

Social Bond Framework

Issuers should publish a framework outlining how their bond issuance aligns with the four core SBP components.

External Review

Issuers are encouraged to seek external verification of their bond or framework's alignment with the SBP. This can take several forms:

Second Party Opinion (SPO): An independent institution with environmental and social expertise assesses the framework's alignment. This is the most common form.

Verification: Independent verification against specific criteria, often post-issuance regarding use of proceeds or reporting.

Certification: Assessment against a formal standard (less common currently for social specifically).

Rating/Scoring: Evaluation by rating agencies or specialised providers assessing the social quality/impact or SBP alignment.

Eligible Social Projects and Target Populations

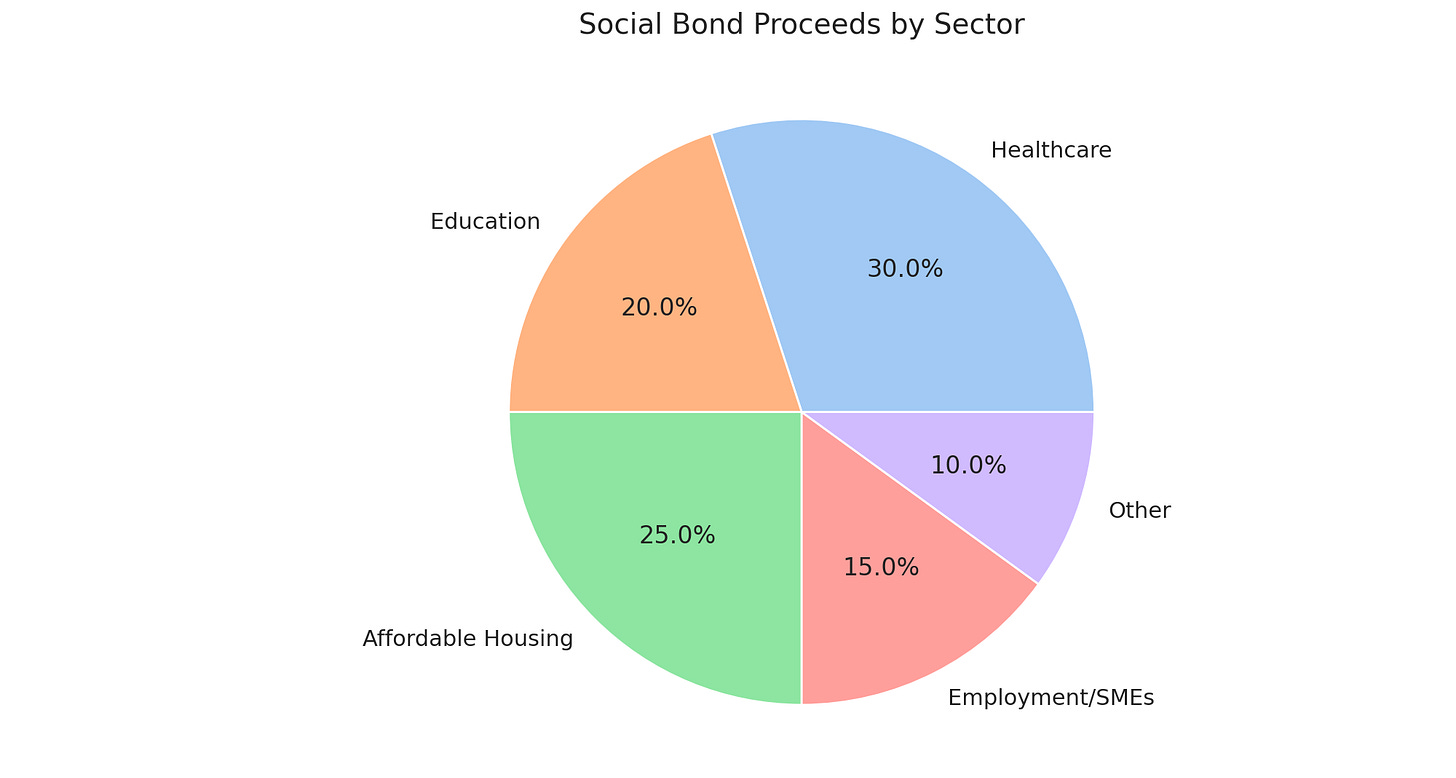

The definition of 'social benefit' is broad, reflecting the diverse challenges societies face. The SBP provide an illustrative list of Eligible Social Project categories, including, but not limited to:

Affordable Basic Infrastructure: Such as clean drinking water, sanitation, transport, clean energy access, particularly for underserved areas.

Access to Essential Services: Including healthcare (hospitals, clinics, prevention programmes), education (schools, vocational training), financial services (microfinance, access for unbanked).

Affordable Housing: Projects providing safe, affordable accommodation for low-income individuals or families.

Employment Generation: Including programmes designed to prevent or alleviate unemployment, especially resulting from socioeconomic crises, potentially through SME financing and microfinance that demonstrably leads to job creation or preservation.

Food Security and Sustainable Food Systems: Projects enhancing access to safe and nutritious food, supporting resilient agriculture, reducing food loss, and improving productivity for small-scale producers.

Socioeconomic Advancement and Empowerment: Initiatives promoting equity, reducing income inequality, and facilitating participation in society and the economy for marginalised groups.

Crucially, these projects should primarily benefit specific Target Populations. The SBP again provide examples:

People living below the poverty line.

Excluded or marginalised populations/communities.

People with disabilities.

Migrants and displaced persons.

Undereducated individuals.

Underserved populations (lacking access to essential goods/services).

Unemployed individuals.

Women and/or sexual and gender minorities (often facing specific barriers).

Ageing populations and vulnerable youth.

Other vulnerable groups (e.g., victims of natural disasters).

The identification of both the project category and the specific target population is fundamental to demonstrating the social intentionality of the bond.

Distinguishing Social Bonds from Related Instruments

The sustainable finance market features several related 'labelled' bonds. Understanding the distinctions is important:

Green Bonds: Proceeds are earmarked exclusively for projects with clear environmental benefits (e.g., renewable energy, energy efficiency, pollution prevention, biodiversity). Governed by the ICMA Green Bond Principles (GBP).

Social Bonds: Proceeds are earmarked exclusively for projects with clear social benefits, targeting specific populations. Governed by the ICMA Social Bond Principles (SBP).

Sustainability Bonds: Proceeds finance a mix of both Green and Social projects. They must align with both the GBP and SBP regarding project eligibility, selection, management of proceeds, and reporting for their respective green and social components. Governed by the ICMA Sustainability Bond Guidelines (SBG).

Sustainability-Linked Bonds (SLBs): These are fundamentally different. Proceeds are not earmarked for specific projects but can be used for general corporate purposes. Instead, the bond's financial characteristics (e.g., coupon rate) are linked to the issuer achieving predefined, ambitious Sustainability Performance Targets (SPTs) measured by Key Performance Indicators (KPIs). Governed by the ICMA Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles (SLBP).

While distinct, these instruments collectively contribute to the broader goals of sustainable development. An issuer chooses the label based on the primary objective of the underlying projects or, in the case of SLBs, their overall corporate sustainability strategy.

The Social Bond Market

The Social Bond market, while younger and smaller than the Green Bond market, has experienced significant growth, particularly accelerated by the need to address the socioeconomic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Market Size and Growth

Tracking precise figures can vary slightly between data providers due to methodology differences. However, reports indicate substantial growth. For instance, estimates for 2024 Social Bond issuance range from approximately USD 169 billion (Bloomberg data cited by Natixis) to USD 251 billion (MainStreet Partners). While Sustainability Bond issuance dipped in 2024, Social Bonds showed resilience or strong growth depending on the source. The combined Green, Social, and Sustainability (GSS) bond market reached nearly USD 1 trillion in 2024, signifying its overall importance. Social loans are also gaining traction, albeit from a smaller base.

Key Issuers

Historically, supranational institutions (like the World Bank/IFC, African Development Bank, Asian Development Bank) and government agencies were dominant issuers, leveraging Social Bonds for large-scale development projects and crisis response. Increasingly, however, we see issuance from:

National and Sub-national Governments: Funding public services, affordable housing, or employment schemes.

Corporates: Addressing social aspects within their value chains, workforce, or communities (e.g., access to healthcare for employees, ethical sourcing, community investment).

Financial Institutions: On-lending to social enterprises, SMEs creating jobs, or financing affordable housing portfolios.

Investor Appetite

Demand for Social Bonds is driven by several factors:

Alignment with Mandates: Growing number of institutional investors with dedicated ESG or impact investing mandates.

Impact Measurement: Desire for investments that demonstrate tangible positive social outcomes alongside financial returns.

Diversification: Offers diversification within fixed-income portfolios.

Reputational Benefits: Associating with investments that address societal needs.

Regulatory Drivers: Increasing focus from policymakers on channelling private capital towards social goals.

Structuring and Issuance Process

Issuing a Social Bond typically involves these steps:

Develop a Social Bond Framework: The issuer defines its social objectives, eligible project categories, target populations, process for project selection, method for managing proceeds, and commitments regarding allocation and impact reporting, aligning with the ICMA SBP.

Seek External Review (Recommended): Obtain a Second Party Opinion (SPO) or other form of review on the Framework to provide independent validation for investors.

Issue the Bond: Standard bond issuance process through capital markets (public offering or private placement), incorporating the Social Bond characteristics and referencing the Framework and SPO in documentation.

Allocate Proceeds: Allocate funds raised to Eligible Social Projects according to the Framework. Manage unallocated proceeds appropriately.

Report: Annually report on the allocation of proceeds until fully disbursed. Annually report on the social impacts of the funded projects throughout the life of the bond. Post-issuance verification of allocation and impact reporting by a third party is also increasingly common.

Benefits of Issuing and Investing in Social Bonds

For Issuers:

Access to Capital: Taps into a dedicated and growing pool of ESG/impact-focused capital.

Diversification of Funding Sources: Broadens the investor base beyond traditional bond buyers.

Enhanced Reputation: Signals commitment to social responsibility and stakeholder well-being.

Improved Stakeholder Engagement: Can strengthen relationships with employees, communities, customers, and investors.

Alignment with Strategy: Provides a tool to finance and highlight corporate social responsibility (CSR) or sustainability strategies.

For Investors:

Meeting ESG/Impact Mandates: Provides credible instruments to fulfil sustainable investment objectives.

Positive Social Impact: Allows capital deployment towards measurable social outcomes.

Transparency and Reporting: Offers greater insight into the use of funds and their impact compared to conventional bonds (when SBP are followed).

Risk Management: Addressing social issues can sometimes mitigate long-term risks (e.g., social unrest, reputational damage).

Comparable Financial Returns: Generally offer similar risk/return profiles to conventional bonds from the same issuer.

Challenges

Despite the growth and potential, the Social Bond market faces hurdles and requires careful navigation:

Impact Measurement and Reporting: This remains the most significant challenge.

Quantification: Measuring social outcomes (e.g., improved health, empowerment) is inherently more complex than measuring environmental metrics (e.g., tonnes of CO2 avoided).

Standardisation: Lack of globally agreed, standardised metrics for social impact makes comparison difficult. While frameworks like the IFC's Harmonised Framework for Impact Reporting exist, adoption varies.

Outputs vs. Outcomes vs. Impact: Reporting often focuses on outputs (e.g., number of houses built) rather than outcomes (e.g., improved living conditions, reduced homelessness) or impact (longer-term societal change attributable to the project, accounting for factors like deadweight and attribution).

Cost and Capacity: Robust impact measurement and reporting require resources and expertise that some issuers may lack.

'Social Washing': The risk that issuers overstate or misrepresent the social benefits of their projects, or issue bonds without genuine commitment to social goals, thereby damaging market integrity. Adherence to SBP and robust external review helps mitigate this, but vigilance is needed.

Defining 'Social' and Additionality: Ensuring that funded projects deliver genuine, additional social benefits beyond 'business as usual' can be complex. The breadth of eligible categories requires careful scrutiny to ensure focus and materiality. Some social themes (e.g., relating to specific minority groups) can also carry political sensitivities for some investors.

Data Availability and Comparability: Lack of long-term data on the financial and social performance of Social Bonds can be a barrier for some investors, especially concerning credit risk perceptions if projects are not inherently revenue-generating (though the bond is typically recourse to the issuer).

Scalability and Project Pipeline: Ensuring a consistent pipeline of high-quality, eligible social projects can be challenging for some issuers.

Liquidity: While improving, the secondary market liquidity for some Social Bonds may be lower than for conventional benchmark bonds.

Addressing these challenges, particularly around impact reporting standardisation and credibility, is crucial for the market's continued maturation and ability to genuinely contribute to social progress.

Opportunities

The future for Social Bonds appears promising, driven by ongoing trends and emerging opportunities:

Increased Corporate Issuance: As companies integrate social factors more deeply into their core strategies, expect more corporates to use Social Bonds beyond traditional development finance institutions.

Thematic Focus: Growth in bonds targeting specific social themes like gender equality (Gender Bonds), health outcomes, education access, or supporting a 'Just Transition' in the shift to a low-carbon economy.

Integration with Sustainability Goals: Closer alignment with national and international goals like the SDGs, potentially driven by evolving regulations and taxonomies (though social taxonomies lag behind green ones).

Improved Impact Reporting: Continued efforts by ICMA, development banks, and industry players to harmonise impact metrics and methodologies, potentially leveraging technology (e.g., better data platforms, though AI/blockchain applications seem more nascent here than perhaps for SLBs).

Regulatory Tailwinds: Potential for supportive policy measures encouraging social investment, although direct incentives for Social Bonds are less common than for Green Bonds in many jurisdictions currently.

Innovation: Exploration of new structures or blended finance models incorporating Social Bond principles to mobilise capital for harder-to-finance social projects.

Investor Sophistication: Investors are becoming more discerning, demanding greater transparency and more robust impact data, which will drive market quality upwards.

The trajectory suggests Social Bonds will become an increasingly integral tool for financing a more equitable and sustainable world, provided the market maintains its focus on transparency and demonstrable impact.

Real-World Examples and Case Studies

International Finance Corporation (IFC)

A pioneer and frequent issuer. IFC established its Social Bond Programme in 2017. Proceeds finance projects aligned with the SBP, focusing on areas like access to essential services (energy, healthcare, water), SME financing (especially women entrepreneurs), and affordable housing in emerging markets. Their reporting often uses the Harmonised Framework. For FY19, they reported USD 823 million committed from social bond proceeds to 31 projects.

Danone (2018)

Notable as an early corporate issuer. Their EUR 300 million bond (approx. USD 355 million at the time) focused on financing research for food security, supporting small-scale producers in their supply chain (socioeconomic advancement), and responsible production practices.

COVID-19 Response Bonds (2020 onwards)

The pandemic triggered significant issuance.

African Development Bank (AfDB): Issued a landmark USD 3 billion 'Fight COVID-19' Social Bond in March 2020, the largest Social Bond at the time, to help alleviate the economic and social impacts across Africa.

Governments and Agencies: Many governments used Social Bonds to fund healthcare system responses, support for unemployed individuals, and aid for struggling SMEs.

Kookmin Bank (South Korea, 2020): Issued a USD 500 million Sustainability Bond (with significant social components) primarily for SME support related to the pandemic crisis.

Affordable Housing

Numerous housing associations, municipalities, and specialised lenders issue Social Bonds specifically to finance the development or provision of affordable housing units, directly addressing SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities).

Note on Social Impact Bonds (SIBs)

It is crucial to distinguish Social Bonds (use-of-proceeds instruments) from Social Impact Bonds (SIBs). SIBs are typically pay-for-success contracts where private investors fund a social intervention delivered by a service provider. Repayment (often with a return) from a government or outcome funder is contingent on achieving pre-agreed, measurable social outcomes. Examples include the Educate Girls DIB in India or homelessness reduction programmes. While both aim for social good, their structure, funding mechanism, and risk profile are distinct.

Role in Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

Social Bonds are intrinsically linked to achieving the UN SDGs. The estimated financing gap to meet the SDGs by 2030 runs into trillions of US dollars annually. Public funds alone are insufficient. Social Bonds provide a critical mechanism to channel private capital towards SDG-aligned objectives.

The eligible project categories outlined in the SBP map directly onto numerous SDGs:

SDG 1 (No Poverty): Projects targeting low-income populations, microfinance.

SDG 2 (Zero Hunger): Food security and sustainable agriculture projects.

SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-being): Access to healthcare, essential medicines, R&D.

SDG 4 (Quality Education): Access to education and vocational training.

SDG 5 (Gender Equality): Projects specifically targeting women's empowerment or access to services/finance.

SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth): Employment generation programmes, SME financing.

SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities): Projects targeting marginalised/excluded groups, promoting socioeconomic inclusion.

SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities): Affordable housing, basic infrastructure (water, sanitation, transport).

By requiring clear use of proceeds and impact reporting, Social Bonds offer investors a way to align their portfolios with specific SDGs and track their contribution, moving beyond broad ESG screening towards targeted sustainable development finance.

Ending Note

Social Bonds have firmly established themselves as a valuable instrument within the sustainable finance toolkit. Their offer is, channelling private capital towards pressing social needs while providing investors with market-based returns and transparent reporting on impact. Their growth trajectory underscores the increasing desire among issuers and investors to align financial activities with positive societal outcomes.

However, the path forward requires continuous vigilance and improvement. The integrity of the market hinges on robust adherence to the Social Bond Principles, particularly concerning the transparency and credibility of project selection and impact reporting. Addressing the challenges around measuring and standardising social impact is paramount to avoid 'social washing' and ensure capital flows to initiatives that genuinely make a difference.

Looking ahead, as awareness grows and methodologies mature, Social Bonds have the potential to play an even greater role in financing solutions to complex global challenges, from poverty reduction and healthcare access to fostering inclusive economies and supporting vulnerable populations. They represent more than just a financial instrument; they are a mechanism for embedding social value into the heart of capital markets, contributing, bond by bond, to building a more just and sustainable future for all. The wisdom lies not just in mobilising the capital, but in ensuring it truly serves humanity.